Compliance vs COMMITMENT

Stephen Jay Gould, former Harvard University professor and leading evolutionary biologist, said, “I am somehow less concerned with the weight and convolution of Einstein's brain, than I am in the certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in the cotton fields and sweatshops.” That is a powerful statement, perhaps suggesting that we can’t see the forest for the trees, as goes the proverb.

Einstein’s brain, and trees, are but technical minutiae when compared with the larger view of untapped talent and arboreal beauty. Is it possible that in the pursuit of organizational excellence we focus too much on the technical details? Organizations clearly progressing on their journey toward excellence, unimpeded by the friction caused by the “flavor of the month,” understand this clearly—if not explicitly, then certainly intuitively. Please allow me to illustrate.

There is an imposing force against real organizational excellence, but it is not often viewed as such. As a matter of fact, there are organizations that boast its perceived virtue. I speak of compliance. One definition of compliance is “excessive acquiescence.” It stands to reason, then, that compliance by its very nature requires constant oversight and monitoring. In essence, it requires policing. In other words, when the boss leaves the room, compliance leaves the room with the boss.

As an example, when traveling the highway, GPS alerts us to the presence of a speed trap. We slow down. Having passed the speed trap, it is no longer a threat to our behavior of speeding so we now return to excessive acceleration. To be clear, compliance is a behavior. Ken Snyder, executive director of the Shingo Institute, can often be heard saying, “Culture is the sum of the behaviors of the people within an organization.” Personally, I prefer to think of culture as the mean of the behaviors of the people within an organization. Although a meaningful descriptive statistic, the sum, by its very nature, obfuscates outliers. Whereas the mean explicitly accounts for them within the context of a normal distribution, or bell curve. We’ll come back to this later.

Another behavior, the opposite of compliance, is commitment. A leading definition of commitment is “the state or quality of being dedicated to a cause, activity.” Commitment is typically associated with a strong personal and often emotional connection to a purpose or objective to which one aligns his or herself. Commitment is embodied by an unwavering belief in the purpose or objective. While the Titanic was sinking, it is said that the musicians stayed and played various tunes to help calm the passengers’ anxiety and panic. Rather than run and panic as many others did, they felt it incumbent upon themselves to provide a calming presence. That they were in mortal danger demonstrates commitment rather than compliance. No one made them stay and play. When the boss leaves the room, commitment stays in the room.

Although this example is contested for its veracity and, therefore, is often hotly debated, it illustrates the difference between commitment and compliance. When the boss leaves the room, compliance leaves the room. When the boss leaves the room, commitment stays in the room.

So, let’s think of this in terms of the Shingo Guiding Principle Improve Flow and Pull. Flow is velocity through the value chain. The ideal is one-piece flow. Pull is an understanding of true demand and allowing that demand to dictate production. Make to order is a pull system. Make to stock is a push system. Push is the opposite of pull. Improve Flow and Pull is an extremely important concept when it comes to commitment versus compliance. To understand the relationship between Improve Flow and Pull and commitment versus compliance, we need to understand the difference between organizations that are technically competent (a focus on the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain or trees), and those that are culturally competent (talent in the cotton fields and sweatshops or the forest).

Organizations that are technically competent understand all the tools of Lean, continuous improvement, six sigma, and other waste-reduction methodologies. They typically have a good understanding of those tools and how to use them. Although well intended, they have a push system that is focused on compliance with respect to use of the tools of these various methodologies. For example, let’s consider an organization that has deployed 5S. Perhaps managers enforced each of their teams to go through the steps of 5S. When it comes to the Sustain step, teams falter and weekly check sheets come in at the end of the week or month as a means of “just getting it done” or checking the box.

Another example of compliance I love is suggestion systems. These systems are put in place and everyone is given a target number of suggestions to complete for the month. Nothing happens all month, and then a slug of suggestions comes through at the end of the month, a good portion of which are meaningless. The box is being checked because, at the end of the month, the boss is in the room. Compliance kicks in.

Dan Fleming, a certified Shingo facilitator and Shingo examiner I truly admire, taught me my favorite question to ask at the gemba: “Who is the data for?” or “Who is this huddle board for?” The answer to this question will often help you know if the organization’s culture is one of commitment or compliance. It is not unusual to hear responses like, “I don’t know,” or “It’s for management.” These are indicators of compliance. The boss has an expectation but he or she may not be in the room.

I have been involved with an organization for three years. They were really struggling with their journey toward excellence. Key leaders within the organization persisted and persisted. They understood they were looking for commitment in their workforce. I was there early September of this year. They shared that in the month of August, they had slightly more than 2,500 improvement suggestions for the month completed, not suggested. For an organization of 830 people, that’s an average of three improvements per individual, for that month. They are actively engaged in building an organization of commitment knowing that they will see an increase in the number of completed suggestions per individual and an increase in the quality of those suggestions as well. They also, as I recall, don’t have a target number of suggestions for each individual to submit on some measure of frequency.

To drive their aspirations, the organization is having more kaizen events, which are very well planned and well executed. And they are for a purpose. The data shows that when a team member or manager is involved in a meaningful and successful kaizen, they generate five times more improvement suggestions than their peers. Experience creates belief. Belief generates behaviors. Behaviors produce results. For good or bad. If you want good results, create experiences that help shift paradigms and develop new beliefs. Create experiences that create commitment.

In another recent example, I had the opportunity to participate in an organizational excellence assessment (not a challenge for the Shingo Prize), where the organization understood that the mean of the behaviors of the people within an organization is its culture. They understood that outliers below the mean had a negative influence on the mean, or a negative influence on the culture. In most of the interviews and meetings we had with the organization’s managers and executives, they talked about these outliers and how they were focused on creating experiences that helped move people closer to the mean. I was impressed that there was little talk of termination, and then only as an absolute last resort. They were highly focused on providing positive experiences that would change beliefs, which would in turn influence behaviors, and thus produce better results. Some of the success stories that were shared were inspiring. Moreover, at different huddles we saw some of those previously considered outliers actively involved in the huddles. The organization understands the power of commitment and is working to drive a culture of people that are committed to Creating Value for the Customer by being better at what they do every day.

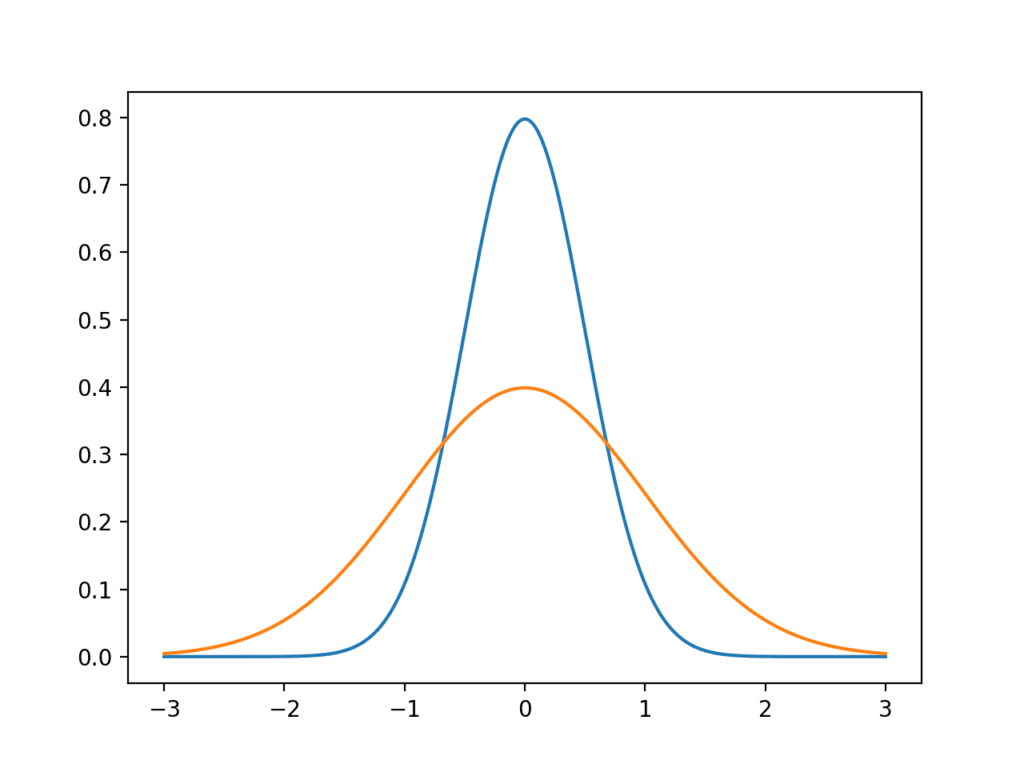

So, going back to culture as the mean of the behaviors of the people within an organization, let’s refer to the two distributions below.

If the two distributions in the illustration represent culture, the distribution represented by the orange curve would suggest a culture of compliance. That is, because people are being compliant and are not committed to the purpose of the organization, there is a good deal of variation of behaviors in the distribution of people within the culture. A culture of commitment, represented by the tall, narrow blue curve, suggests that there is less variation in the behaviors of the people within the culture because they are committed to the purpose of the organization. When people are committed, they are typically open to knowing what they can do to be more supportive of the purpose of the organization. In short, they are willing to learn. Being willing to learn leads to being willing to change.

Now this all sounds idealistic, and it is. But let’s also be realistic. Just because an organization strives for a culture of commitment does not mean it does not have its hiccups. However, the ability to identify opportunities for improvement and to accept them for what they are (to see reality) makes such organizations much more nimble and able to rapidly overcome the challenges they are certain to deal with in the course of doing business.

One additional thought before I conclude. To be clear, I am not talking here about regulatory compliance, which is a different discussion altogether.

Compliance equals a push system for Lean tools. Commitment is a pull system for Lean tools. Technical competence in Lean, versus cultural competence, pulls Lean tools as the organization grows. The weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain may certainly be interesting, but for my money, I’ll put my efforts into the untapped talent in the cotton fields and sweatshops, where commitment awaits a release by a culture that fosters its commitment.